Melanie Klein: Paranoid-Schizoid and Depressive Position

If you’ve ever tried to understand Melanie Klein’s theories, you likely felt overwhelmed by the onslaught of terms such as: the paranoid-schizoid position, depressive position, the good and bad breast, splitting, annihilation anxiety, life and death instinct… 😵💫

She didn’t make it easy to understand her theory.

But that’s a pity, because despite being controversial and weird, there is something interesting to her ideas. So, let’s simplify and clarify her theory to understand why ambivalence is a good thing, where creativity comes from, why someone’s exes may all be narcissists and how all of this applies to… Harry Potter.

You can read any old psychodynamic books looking for flaws (spoiler alert: you’ll find loads, there is a lot to criticise Klein and Kleinians for) or you can read them looking for interesting new ideas that spark your own curiosity. And today, we chose indulging in new weird ideas to see what we can get from them.

I suggest before we try to understand her theory about the paranoid-schizoid and depressive position, we need to take a minute to dive into her remarkable life — because you cannot divorce a theory from its inventor.

Biography

If I had to summarize Melanie Klein’s life in one sentence, it would be: Unrelenting power in the face of hardship. Her forceful, authoritarian, direct personality is what got her through one devastating loss after the other, helped her jump into a very successful career — and also lead to painful alienation in both her professional and private life.

Klein was born in 1882 in Vienna, loses her old father, one sister and brother all before she got married having just turned 21. She soon developed a depression that worsened while raising three children and being her husband’s trailing spouse. She started her own analysis in 1914 with Sandor Ferenczi, read Freud, heard Freud speak for the first time in 1918 — and in that process not just her depression lifted but her life was forever changed.

She started publishing her own papers, divorced her husband, moved first to Berlin, then settled in London. She becomes one of the pioneers to the still new field of psychoanalysis, one of the first to develop the new discipline of child analysis, and used her newly gained insight to become one of the leading contributors to object relations theory (I’ve create an entire video about that). All without a university degree to her name at a time where psychoanalysis was dominated by male medical doctors. Her biography is quite something. The Melanie Klein Trust put together a wonderful timeline if you want to learn more: https://melanie-klein-trust.org.uk/timeline

Klein considered herself a Freudian in many ways — even though she later became the worst rival of his daughter Anna Freud. This showed first and foremost when she took Freud’s most controversial concept and made it the backbone of her theory.

Life and Death Instinct

The foundation of every theory is a certain world view, a certain way of thinking about what it means to be human. One of Klein’s controversial assumptions that underpins her theoretical ideas is the idea of the life and death instinct. This is an idea she took over from Freud, which was also his most controversial idea, that he first discussed in “Beyond the Pleasure Principle” in 1920.

To be precise, Freud didn’t talk about the life and death instinct, he talked about the life and death drive (Lebens- und Todestrieb), or Eros (Libido) and Thanatos. This was the ultimate reformulation of his drive theory, trying to answer the question what internal forces, well, drive the human being.

The death drive can be a tricky subject to wrap your head around but let me give you at least a very brief summary: According to Freud, from the very beginning there is something inside of us that strives toward renewal, creating excitement, and tension (LIFE) and something inside of us that strives towards relief from tension, letting go, returning to an inanimate state (DEATH).

It can be easier to understand drives in action. What might they look like? According to Freud’s previous theory a drive can be directed towards the self or the object. The life instinct (or libido) in action directed towards the self or the object is what we might call “love”, ranging from mature love to dependency, and realistic self-esteem to narcissism. The death drive in action is what we would call aggression, ranging from setting healthy boundaries, achieving mastery, power, solving conflicts to the destruction of others or the self.

There has been a tendency in psychodynamic psychology to move from drives to affect (emotions). And we can see the beginning here in Klein that would then be expanded on by Kernberg. They understand the death drive as our innate capability for destruction, aggression, and hate versus libido as our innate capability for love, reparation, and empathy. This is how Klein turned Freud’s biological concepts into psychological ones.

The integration of and dealing with our death drive or our ability for destruction is a life-long task and early on, in infants Klein thought it is “the primary factor in the causation of anxiety” (p. 41). Someone who hasn’t yet found a way to deal with their death instinct is much more frightened of it. And the first way the ego of the infant, whose primary function is “dealing with anxiety” (p. 4) does to calm the anxiety elicited by the death instinct is the hallmark of Klein’s famed concept of the “paranoid-schizoid position”.

Intermission: Why “Position”?

But before we go there: Why did Klein use the term “position”? Klein’s positions are not developmental steps that you achieve once and keep forever. Her positions are ways of experiencing, making sense of, and dealing with the inner and outer world.

Klein assumed that an ego is present since birth (Freud on the other hand assumed that the ego develops out of the id with time). However, it is not yet integrated, coherent but one of the main functions even of the early ego is to deal with anxiety.

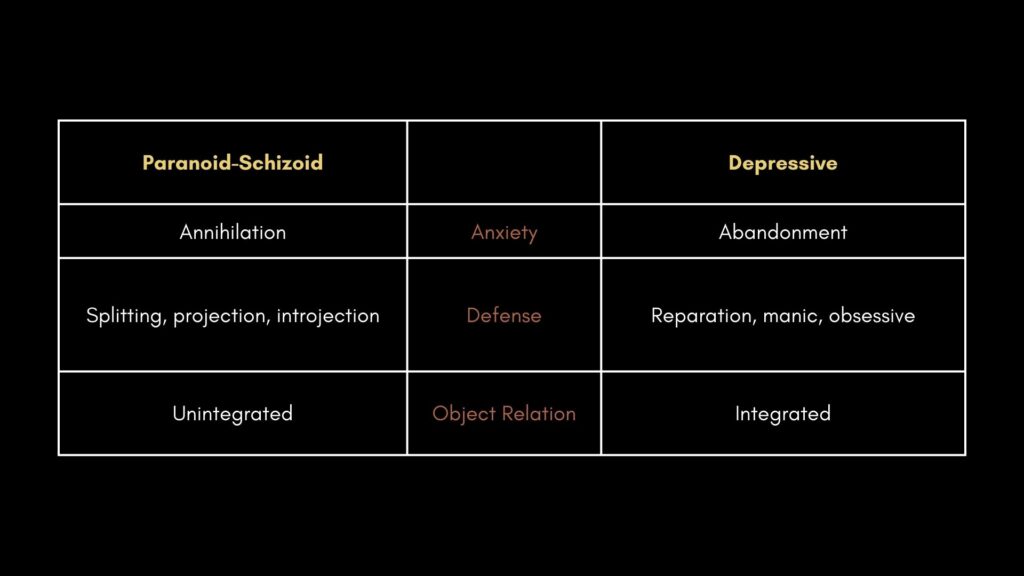

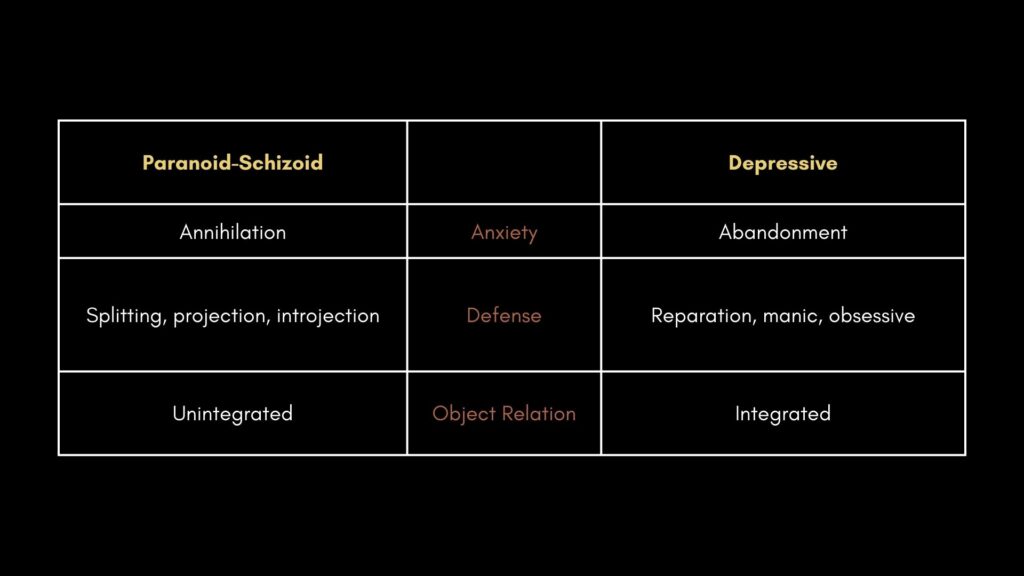

And a position is an attempt of the ego to deal with anxiety elicited by the death instinct through defenses that create characteristic ideas about and relations between the self and another person (we would call that an object relation). A position is a combination of a certain form of anxiety, defenses against it, and a resulting self-object relation. This might all sound quite vague but we’ll clarify what exactly that means when we talk about the two positions in detail.

So keep in mind that positions are states of mind that are there to deal with anxiety and can be inhabited and also abandoned temporarily as we grow older. Now let’s see what those anxieties are that we need to defend against, starting with the paranoid-schizoid position.

Paranoid-Schizoid Position

In 1946, Klein’s paper “Notes on Some Schizoid Mechanisms” hits the British Psychoanalytical Society like another fever dream. It’s considered one of Klein’s most important papers in which she properly introduces the paranoid-schizoid position and the defenses of splitting and projective identification. I do recommend reading this paper, it’s the first one in the collection called “Envy and Gratitude” and actually also the “Envy and Gratitude” paper itself because it’s another expansion on those ideas – it can seem a bit intimidating to dive into original literature but it’s a somewhat doable read, especially if you first read this article and have somewhat of an idea of how to make sense of her terrible terminology.

Over all, the paranoid-schizoid position is a state of mind that, according to Klein, is prevalent in the first three months of life, then gradually decreases throughout childhood and adolescence, and in normal development only reappears occasionally under great stress. It’s assumed to only remain the prevalent state of mind for people suffering from various schizophrenic illnesses.

As we’ve covered before, Klein assumes an innate death instinct and that “…anxiety arises from the operation of the death instinct within the organism” (p. 4). We cannot experience a drive itself but we can experience a drive in action, what it does to us or makes us do, so she continues that this anxiety “is felt as a fear of annihilation (death)”. According to Klein, an infant is afraid of being annihilated, this is a part of what the term “paranoid” refers to. What a start. Luckily that’s not the only thing that is happening, remember there is also the life instinct.

Hanna Segal, one of Melanie Klein’s most famous students, writes: “The immature ego of the infant is exposed from birth to the anxiety stirred up by the inborn polarity of instincts – the immediate conflict between the life instinct and the death instinct. It is also immediately exposed to the impact of external reality, both anxiety-producing, like the trauma of birth, and life-giving, like the warmth, love and feeding received from its mother.” (p. 25)

So, the mind of the newborn, the infant becomes the stage of an existential drama: How can life survive death? How can love win over hate? The ego of the infant has to find a way to manage this anxiety and survive.

Splitting

The first step to save life from death and love from hate is to try to keep them as far away from each other as possible, so that hate doesn’t contaminate love. To do that the ego uses the defense mechanism of splitting, which is the schizoid mechanism. The early ego, that is not integrated itself, splits love from hate, life from death, in order to keep love safe from the hate that would otherwise destroy and annihilate it.

From an outside perspective, it’s so hard to get an idea what exactly is going on in an infant. Early mental life must be chaos. Imagine no language, no memory, just bodily sensations like hunger or tiredness with no way to make sense of them, which you could imagine might feel like a danger of annihilation. The link between aggression and hunger is clear to anyone who has ever been hangry. We can observe that infants seem to live in one of two states: either they’re fed, calm, comfortable or they are hungry, agitated, uncomfortable. Which kind of maps onto the life and death instinct. To split chaotic experiences into two, is not a bad way to make sense of the chaos and feel less anxious.

Melanie Klein gets a bad rep for apparently not caring about the impact of the external world and the real mother – but, if you read her papers after you’ve read this article – I don’t think you’d agree that she doesn’t take it into account. So let’s take a look at what the next defense against annihilation anxiety is and what the mother has to do with it.

Projection

The first step to lessen annihilation anxiety is splitting to keep the death instinct from destroying the life within. In order to create even more distance between love and hate, the ego uses another defense mechanism namely projection. This is where the good and bad breast come in. The infant experiences good and bad states in connection to the breast or the bottle. It’s the first relation between the self and a so-called part-object (part-object because the breast or bottle is just a part of the whole object, the whole person), even though the infant still experiences the part-object as a part of the self, there is not yet an awareness that the breast belongs to the mother who is a separate person.

If the breast provides milk at the right time, in the right quality, with the right speed – the self (the infant) feels good and experiences the breast as good. If the breast doesn’t give milk, or not at the right time, not in the right quality, or not at the right speed – the self feels bad and experiences the breast as bad. In simple terms, to gain even more distance from one’s own destructive impulses, the ego projects (puts) those hateful feelings into the bad breast. A part of the death instinct is then projected out. It’s saying: “No, no, actually there is nothing destructive inside of me, it’s out there where I can fight and destroy it.”

This is where Klein completes the “paranoid” bit when she expands that “anxiety arises from the operation of the death instinct within the organism, is felt as a fear of annihilation (death) and takes the form of fear of persecution.” (p. 4)

If any of you have seen my video about the psychoanalysis of Dwight Schrute from The Office, this is a nice case study where I explain more about the paranoid personality style if you are interested:

Consequently, all the infant’s hate is directed against the bad breast. It bites it, pinches, screams at, and hits that which it believes is out to destroy him. And on the other hand it desperately needs and idealizes the good breast, because “it is not only food he [the infant] desires; he also wants to be freed from destructive impulses and persecutory anxiety” p. 185. The good breast is the saviour and the bad breast the persecutor. The consequence of splitting, the schizoid mechanism, is that we have split object relations, there is no integration.

Splitting and projection not just allow to keep love and hate apart from each other but also allow to deny that the bad object and destruction even exist. And here Melanie Klein says something so beautifully:

“Omnipotent denial of the existence of the bad object and of the painful situation is in the unconscious equal to annihilation by the destructive impulse. It is, however, not only a situation and an object that are denied and annihilated – it is an object-relation which suffers this fate; and therefore a part of the ego, from which the feelings towards the object emanate, is denied and annihilated as well.” (p. 7)

This nicely links to Jung’s idea about the creation of the shadow it seems. Every time that the destructive impulses become too much, there is another split in the object and the ego, and potentially more and more potency, strength, and knowledge denied and lost.

Introjection

For love to win over hate, the infant can try to get rid of the death drive or at least parts of it, which we have talked about with the mechanisms of splitting and projection. But it can also try to strengthen the life instinct within, which happens through introjection of the good breast.

The life instinct is first projected into the good breast and through the gratifying experience re-introjected into the ego. This process of balanced projection and introjection helps to establish what is called “the good inner object” within the self.

It might sound a bit strange but at the end of the day, the good inner object is the inner voice that says “You might not be perfect but you’re a good person” or “You’ve worked hard today, it’s time for a cup of tea” or critical in a constructive way like “You don’t need to act this way, this doesn’t align with who you are on the inside.”

And as the good inner object gets stronger, eventually the confidence that life can overcome death, that love is more powerful than hate grows. This is necessary to create coherence, integration, and counteract the splitting which could cause disintegration. When the infant feels it less necessary to keep love and hate that far apart (because it no longer feels like it will be destroyed) it slowly starts realizing that the good and bad breast was the same all along, which throws it into the next kind of anxiety and the depressive position.

Depressive Position

A good illustration of how we move from the paranoid-schizoid to the depressive position is Harry Potter: In the beginning love and hate are clearly separated. It allows us to fully identify with Harry Potter and despise Voldemord and Snape. Once Harry reconnected enough with his good inner objects [parents in the mirror] more complexity becomes possible. We start seeing that things aren’t as black and white: We get to know Tom Riddle, the human behind Voldemord and can empathise with his traumatic past. Then, revealing Snape’s backstory might be one of the most moving twists in this book. Beyond the hostile exterior, there is a complex mixture of love, loyalty, and the ultimate sacrifice. And I assume anyone reading the books felt guilty about how they hated Snape and wanted to make reparations. It’s no accident that Snape’s uttering of “Always” has been inked into many Potter fans. And also our hero Harry gains in complexity, when it becomes evident that some of Voldemord’s badness is within himself.

As we’ve discussed before, the paranoid-schizoid position is activated when we are in a state of fight, assertion, when we don’t know if we survive, as this position fends off annihilation anxiety. Klein writes: “The fact that a good relation to its mother and to the external world helps the baby to overcome its early paranoid anxieties throws a new light on the importance of its earliest experiences.” (p. 285, Love, Guilt, and Reparation)

If we received love, good enough care, and established a first basis of the good inner object in the first few months, the fear of death gradually diminishes. There is enough goodness inside of us to neutralize more of our destructive impulses. With decreasing annihilation anxiety the need for splitting and projection diminishes and we are able to perceive ourselves and others in a whole new way: Others get to be themselves and not just a repository for parts of us. We start realizing that the good and bad breast belong to the same person. Our care-giver didn’t frustrate us because they are evil, rather they are imperfect, fallible people – just like us. Likewise, we start realizing that we have the capacity for hate and destruction. It’s part of us and we are not just all good and purely the victim of evil out there. This then sets off another type of anxiety.

Klein actually developed the concept of the depressive position before the paranoid-schizoid position mostly in her paper “A Contribution to the Psychogenesis of Manic-Depressive States” in 1935. The depressive position is called “depressive” because it deals with the depressive anxiety of losing the good object and being abandoned.

When we realize that the good and bad object are the same person, we discover the concept of ambivalence. From a modern perspective ambivalence means having loving and hateful feelings towards the same person and understanding it this way, we can see that it’s actually a developmental achievement. If we experience a reasonable level of ambivalence, we have arrived in reality where nothing is black-or-white, we have developed the mental capacity to contain complexity. Which also means we have taken a step back from the illusions of omnipotence and have come to realize our dependence.

The great loss of this position is that we need to let go of our belief in paradise and perfection. In the paranoid-schizoid position a perfect union with a perfect object was possible — now we have to settle for good-enough.

When we realize that we carry destructive impulses inside of us, that we are also good and bad, we feel great remorse and guilt over how we treated the “bad” object. The paranoid-schizoid position was all about the self and saving the self from destruction, even the part-object was just another extension of the self to store the “bad parts”. Now the depressive position is focused on the object (and the self) and is about saving the good (inner) object from destruction. Therefore, we start to make reparations. The defenses of this position have a lot to do with finding ways to navigate our feelings of guilt and manage our destructive impulses, to allow for satisfying relationships with others. If this position is worked through well enough, we can take on responsibility for our own aggression, find compromises with others, while not losing us in a net over overwhelming guilt, or manically abdicating responsibility all together. This position requires us to use our new capabilities to solve inner conflicts and find new ways to deal with frustrations. Therefore, if we navigate and work through this position well, we develop the capacity for mature love, empathy, responsibility, and creativity.

There are a bunch of other concepts to dive into, such as projective identification, envy, psychopathology, the dangers of excessive introjection and projection, her understanding of the super-ego, and much more but I’m going to end the aricle here with criticism about Kleinians and their theories.

Criticism

My first personal criticism is the terminology. I dislike the terms Klein chose, it makes it more complicated than it needed to be in my opinion and makes it feel like she needed to impress the other male, university-educated analysts to compensate. Also I cannot read her (or other Kleinians) case studies, even just in the papers I mentioned in this article. They are full of very primitive terms, everything is about penises, vaginas, faeces – I don’t find that appealing nor helpful.

The second criticism is about treatment. I have never been in Kleinian analysis but from talking with some Patreons in my book club I’ve heard that their approach is very direct to put it lightly. They interpret ruthlessly. Someone benefitted from the bluntness of it, and another equated it to a rectal exam. I recently came across an article written by someone who recognized themselves in a case study written by a Kleinian analyst, I’ll link it below, that was quite a read. As I said, I never worked with a Kleinian analyst, but this is the criticism I heard and can imagine well from studying Klein.

Then of course there is a lot of criticism on her theory, from being too focused on aggression, not taking the real caregivers into account enough, misrepresenting concepts. And it’s a little ironic that Klein’s view split the British psychoanalytic society into two camps. The Kleinians and the followers of Anna Freud, with one of her harshest critics being Klein’s own daughter Melitta.

In general, we need to take into account that the followers of a thinker tend to be more radical than the thinker herself. Theorists, such as Melanie Klein, Sigmund Freud, Heinz Kohut, or Alice Miller developed theories that are based on their own personality style and struggles (as Nancy McWilliams put it), either to validate or to balance them.

Therefore, studying a multitude of theories is a good idea, so that you have a wide buffet to pull from when trying to understand your patients (and yourself).